Is An Entity More Likely To Attach Itself To A Person An Animal Or An Object

Chapter 3. The Self

The Cerebral Cocky: The Self-Concept

- Define and depict the self-concept, its influence on data processing, and its multifariousness across social groups.

- Describe the concepts of self-complication and cocky-concept clarity, and explicate how they influence social cognition and behavior.

- Differentiate the various types of cocky-awareness and self-consciousness.

- Describe cocky-sensation, cocky-discrepancy, and self-affirmation theories, and their interrelationships.

- Explore how we sometimes overestimate the accuracy with which other people view us.

Some nonhuman animals, including chimpanzees, orangutans, and mayhap dolphins, have at least a archaic sense of self (Boysen & Himes, 1999). Nosotros know this because of some interesting experiments that accept been done with animals. In ane written report (Gallup, 1970), researchers painted a red dot on the forehead of anesthetized chimpanzees and then placed the animals in a muzzle with a mirror. When the chimps woke up and looked in the mirror, they touched the dot on their faces, non the dot on the faces in the mirror. This activeness suggests that the chimps understood that they were looking at themselves and not at other animals, and thus we tin can presume that they are able to realize that they be as individuals. Well-nigh other animals, including dogs, cats, and monkeys, never realize that it is themselves they run into in a mirror.

Getting ready by Flavia (https://www.flickr.com/photos/mistressf/3068196530/) used under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/two.0/). Mirror mirror by rromer (https://world wide web.flickr.com/photos/rromer/6309501395/) used nether CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/). Quite Reflection by Valerie (https://www.flickr.com/photos/ucumari/374017970/in/photostream/) used under CC Past-NC-ND 2.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/past-nc-nd/2.0/). Toddler in mirror by Samantha Steele (https://www.flickr.com/photos/samanthasteele/3983047059/) used nether CC BY-NC-ND ii.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/past-nc-nd/two.0/)

Infants who have like ruddy dots painted on their foreheads recognize themselves in a mirror in the same way that chimps practice, and they do this by most 18 months of age (Asendorpf, Warkentin, & Baudonnière, 1996; Povinelli, Landau, & Perilloux, 1996). The kid'southward knowledge about the self continues to develop as the kid grows. By two years of age, the infant becomes enlightened of his or her gender as a boy or a girl. At age four, the child'south self-descriptions are likely to exist based on physical features, such every bit hair color, and past about age six, the kid is able to understand bones emotions and the concepts of traits, beingness able to brand statements such every bit "I am a dainty person" (Harter, 1998).

By the time children are in grade schoolhouse, they have learned that they are unique individuals, and they can think virtually and analyze their own behavior. They also begin to show sensation of the social situation—they understand that other people are looking at and judging them the same way that they are looking at and judging others (Doherty, 2009).

Development and Characteristics of the Self-Concept

Part of what is developing in children as they grow is the fundamental cerebral function of the self, known as the self-concept. The self-concept is a noesis representation that contains noesis about the states, including our beliefs about our personality traits, physical characteristics, abilities, values, goals, and roles, also as the knowledge that nosotros exist as individuals. Throughout childhood and adolescence, the self-concept becomes more abstruse and complex and is organized into a variety of unlike cognitive aspects of the self, known every bit cocky-schemas.Children have self-schemas virtually their progress in school, their appearance, their skills at sports and other activities, and many other aspects. In turn, these self-schemas straight and inform their processing of self-relevant data (Harter, 1999), much as we saw schemas in full general affecting our social cognition.

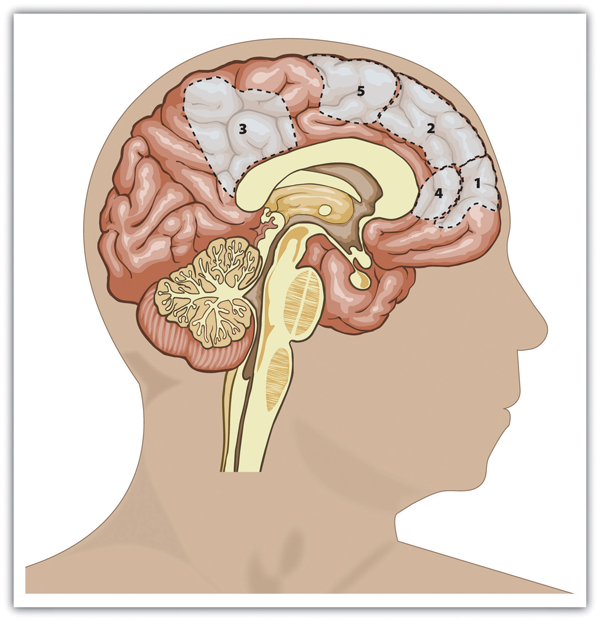

These self-schemas can be studied using the methods that nosotros would use to report any other schema. One approach is to utilise neuroimaging to direct study the self in the encephalon. Every bit you can encounter in Figure 3.3, neuroimaging studies have shown that information nigh the self is stored in the prefrontal cortex, the same place that other information about people is stored (Barrios et al., 2008).

Another approach to studying the self is to investigate how we attend to and remember things that relate to the self. Indeed, because the cocky-concept is the well-nigh important of all our schemas, it has an extraordinary degree of influence on our thoughts, feelings, and behavior. Have you lot ever been at a party where in that location was a lot of noise and bustle, and yet y'all were surprised to discover that you could easily hear your own name being mentioned in the background? Because our own name is such an important part of our self-concept, and because we value information technology highly, it is highly accessible. We are very warning for, and react quickly to, the mention of our own name.

Other research has found that information related to the self-schema is improve remembered than information that is unrelated to it, and that information related to the self can also be processed very quickly (Lieberman, Jarcho, & Satpute, 2004). In one classic study that demonstrated the importance of the cocky-schema, Rogers, Kuiper, and Kirker (1977) conducted an experiment to appraise how college students recalled information that they had learned under different processing atmospheric condition. All the participants were presented with the same listing of xl adjectives to process, but through the use of random assignment, the participants were given i of iv dissimilar sets of instructions almost how to process the adjectives.

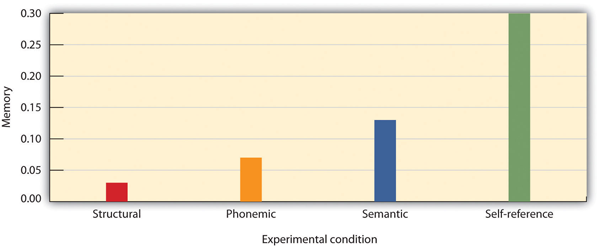

Participants assigned to thestructural chore condition were asked to judge whether the word was printed in uppercase or lowercase letters. Participants in thephonemic job condition were asked whether the word rhymed with another given word. In thesemantic task condition, the participants were asked if the word was a synonym of another word. And in theself-reference task condition, participants indicated whether the given describing word was or was not true of themselves. Later completing the specified task, each participant was asked to recall as many adjectives as he or she could remember. Rogers and his colleagues hypothesized that different types of processing would take different furnishings on retentiveness. Every bit y'all can see in Figure iii.4, "The Self-Reference Effect," the students in the self-reference task condition recalled significantly more than adjectives than did students in any other condition.

The chart shows the proportion of adjectives that students were able to call back under each of four learning conditions. The same words were recalled significantly better when they were processed in relation to the self than when they were processed in other means. Data from Rogers et al. (1977).

The finding thatinformation that is processed in relationship to the self is specially well remembered, known as the cocky-reference effect, is powerful evidence that the self-concept helps us organize and call up information. The next time you are studying, you lot might try relating the material to your ain experiences—the self-reference effect suggests that doing so will help yous meliorate remember the information.

The specific content of our self-concept powerfully affects the way that we procedure information relating to ourselves. But how can we mensurate that specific content? Ane mode is by using self-report tests. One of these is a deceptively simple backup-the-blank mensurate that has been widely used past many scientists to go a motion-picture show of the self-concept (Rees & Nicholson, 1994). All of the 20 items in the mensurate are exactly the same, but the person is asked to make full in a unlike response for each statement. This self-report measure out, known equally the Twenty Statements Test (TST), tin reveal a lot about a person because it is designed to measure out the almost accessible—and thus the nearly important—parts of a person's self-concept. Endeavor information technology for yourself, at least five times:

- I am (please fill in the bare) __________________________________

- I am (please fill up in the blank) __________________________________

- I am (delight fill in the blank) __________________________________

- I am (please fill in the blank) __________________________________

- I am (please make full in the blank) __________________________________

Although each person has a unique self-concept, we can identify some characteristics that are mutual across the responses given by different people on the mensurate. Physical characteristics are an important component of the self-concept, and they are mentioned by many people when they draw themselves. If you lot've been concerned lately that you've been gaining weight, y'all might write, "I am overweight." If you think yous're particularly good looking ("I am attractive"), or if you retrieve you're also short ("I am too brusque"), those things might accept been reflected in your responses. Our physical characteristics are important to our self-concept considering we realize that other people use them to approximate u.s.a.. People often list the physical characteristics that brand them unlike from others in either positive or negative ways ("I am blond," "I am curt"), in part because they understand that these characteristics are salient and thus likely to be used by others when judging them (McGuire, McGuire, Kid, & Fujioka, 1978).

A 2d aspect of the self-concept relating to personal characteristics is made upwards ofpersonality traits—the specific and stable personality characteristics that draw an private ("I amfriendly," "I amshy," "I ampersistent"). These individual differences are important determinants of beliefs, and this aspect of the cocky-concept varies among people.

The remainder of the cocky-concept reflects its more than external, social components; for example, memberships in the social groups that nosotros vest to and care nigh. Mutual responses for this component may include "I am an artist," "I am Jewish," and "I am a mother, sister, daughter." As we will run across afterwards in this chapter, group memberships form an important part of the self-concept because they provide the states with our social identity—the sense of our self that involves our memberships in social groups.

Although we all define ourselves in relation to these three wide categories of characteristics—concrete, personality, and social – some interesting cultural differences in the relative importance of these categories take been shown in people's responses to the TST. For case, Ip and Bond (1995) institute that the responses from Asian participants included significantly more references to themselves equally occupants of social roles (e.1000., "I am Joyce's friend") or social groups (e.g., "I am a member of the Cheng family") than those of American participants. Similarly, Markus and Kitayama (1991) reported that Asian participants were more than twice as probable to include references to other people in their self-concept than did their Western counterparts. This greater emphasis on either external and social aspects of the self-concept reflects the relative importance that collectivistic and individualistic cultures place on an interdependence versus independence (Nisbett, 2003).

Interestingly, bicultural individuals who report acculturation to both collectivist and individualist cultures testify shifts in their self-concept depending on which culture they are primed to call back about when completing the TST. For example, Ross, Xun, & Wilson (2002) found that students born in Communist china but living in Canada reported more interdependent aspects of themselves on the TST when asked to write their responses in Chinese, every bit opposed to English. These culturally different responses to the TST are also related to a broader distinction in self-concept, with people from individualistic cultures often describing themselves using internal characteristics that emphasize their uniqueness, compared with those from collectivistic backgrounds who tend to stress shared social grouping memberships and roles. In turn, this distinction can lead to important differences in social behavior.

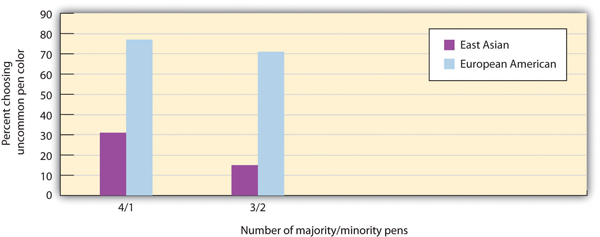

One simple notwithstanding powerful sit-in of cultural differences in self-concept affecting social behavior is shown in a study that was conducted past Kim and Markus (1999). In this study, participants were contacted in the waiting surface area of the San Francisco airport and asked to fill out a short questionnaire for the researcher. The participants were selected according to their cultural background: nearly one-half of them indicated they were European Americans whose parents were born in the Usa, and the other one-half indicated they were Asian Americans whose parents were built-in in People's republic of china and who spoke Chinese at dwelling. Later completing the questionnaires (which were not used in the data analysis except to determine the cultural backgrounds), participants were asked if they would similar to have a pen with them as a token of appreciation. The experimenter extended his or her hand, which contained five pens. The pens offered to the participants were either 3 or four of i color and ane or two of some other colour (the ink in the pens was e'er black). As shown in Figure 3.5, "Cultural Differences in Desire for Uniqueness," and consequent with the hypothesized preference for uniqueness in Western, but non Eastern, cultures, the European Americans preferred to take a pen with the more unusual color, whereas the Asian American participants preferred i with the more common color.

In this study, participants from European American and East Asian cultures were asked to cull a pen equally a token of appreciation for completing a questionnaire. At that place were either four pens of one colour and one of another color, or three pens of one color and ii of another. European Americans were significantly more than likely to choose the more than uncommon pen colour in both cases. Data are from Kim and Markus (1999, Experiment 3).

Cultural differences in cocky-concept have even been found in people's self-descriptions on social networking sites. DeAndrea, Shaw, and Levine (2010) examined individuals' free-text self-descriptions in the Nigh Me section in their Facebook profiles. Consistent with the researchers' hypotheses, and with previous research using the TST, African American participants had the about the most independently (internally) described self-concepts, and Asian Americans had the most interdependent (external) self-descriptions, with European Americans in the middle.

As well every bit indications of cultural diversity in the content of the self-concept, there is likewise prove of parallel gender variety betwixt males and females from diverse cultures, with females, on average, giving more than external and social responses to the TST than males (Kashima et al., 1995). Interestingly, these gender differences have been establish to be more than credible in individualistic nations than in collectivistic nations (Watkins et al., 1998).

Self-Complexity and Cocky-Concept Clarity

As nosotros have seen, the self-concept is a rich and circuitous social representation of who we are, encompassing both our internal characteristics and our social roles. In addition to our thoughts almost who nosotros are right at present, the self-concept also includes thoughts about our past cocky—our experiences, accomplishments, and failures—and virtually our future self—our hopes, plans, goals, and possibilities (Oyserman, Bybee, Terry, & Hart-Johnson, 2004). The multidimensional nature of our self-concept means that nosotros need to consider not just each component in isolation, simply also their interactions with each other and their overall construction. 2 peculiarly important structural aspects of our self-concept are complication and clarity.

Although every homo being has a complex self-concept, there are nevertheless individual differences in self-complication, the extent to which individuals have many dissimilar and relatively independent means of thinking most themselves (Linville, 1987; Roccas & Brewer, 2002). Some selves are more circuitous than others, and these private differences can be important in determining psychological outcomes. Having a complex self means that nosotros take a lot of unlike ways of thinking almost ourselves. For example, imagine a woman whose self-concept contains the social identities of student, girlfriend, daughter, psychology student, and tennis role player and who has encountered a wide variety of life experiences. Social psychologists would say that she has high self-complexity. On the other hand, a man who perceives himself primarily as either a student or as a fellow member of the soccer squad and who has had a relatively narrow range of life experiences would be said to have low self-complication. For those with high self-complexity, the diverse aspects of the self are carve up, as the positive and negative thoughts virtually a particular self-aspect do non spill over into thoughts virtually other aspects.

Research has found that compared with people low in cocky-complexity, those higher in self-complexity tend to experience more than positive outcomes, including college levels of self-esteem (Rafaeli-Mor & Steinberg, 2002), lower levels of stress and disease (Kalthoff & Neimeyer, 1993), and a greater tolerance for frustration (Gramzow, Sedikides, Panter, & Insko, 2000).

The benefits of self-complication occur because the various domains of the self assistance to buffer us against negative events and enjoy the positive events that we experience. For people depression in self-complexity, negative outcomes in relation to one aspect of the cocky tend to have a big affect on their self-esteem. For example, if the only affair that Maria cares about is getting into medical school, she may be devastated if she fails to make it. On the other hand, Marty, who is also passionate about medical school but who has a more circuitous self-concept, may exist meliorate able to adjust to such a blow by turning to other interests.

Although having high self-complexity seems useful overall, it does not seem to help everyone as in their response to all events (Rafaeli-Mor & Steinberg, 2002). People with high self-complexity seem to react more positively to the good things that happen to them but non necessarily less negatively to the bad things. And the positive effects of cocky-complexity are stronger for people who accept other positive aspects of the self every bit well. This buffering issue is stronger for people with loftier cocky-esteem, whose self-complexity involves positive rather than negative characteristics (Koch & Shepperd, 2004), and for people who feel that they have control over their outcomes (McConnell et al., 2005).

Just as nosotros may differ in the complexity of our self-concept, and so we may likewise differ in its clarity.Self-concept clarityis the extent to which 1'due south self-concept is clearly and consistently defined (Campbell, 1990). Theoretically, the concepts of complexity and clarity are independent of each other—a person could have either a more than or less complex self-concept that is either well divers and consistent, or ill defined and inconsistent. However, in reality, they each take similar relationships to many indices of well-being.

For example, equally has been plant with self-complexity, higher self-concept clarity is positively related to self-esteem (Campbell et al., 1996). Why might this be? Perhaps people with higher cocky-esteem tend to have a more well-defined and stable view of their positive qualities, whereas those with lower self-esteem testify more inconsistency and instability in their self-concept, which is then more vulnerable to being negatively afflicted by challenging situations. Consistent with this assertion, cocky-concept clarity appears to mediate the human relationship between stress and well-being (Ritchie et al., 2011).

Also, having a clear and stable view of ourselves can help usa in our relationships. Lewandowski, Nardine, and Raines (2010) found a positive correlation between clarity and human relationship satisfaction, besides as a significant increase in reported satisfaction following an experimental manipulation of participants' cocky-concept clarity. Greater clarity may promote relationship satisfaction in a number of means. As Lewandowski and colleagues (2010) argue, when we have a clear self-concept, we may be meliorate able to consistently communicate who we are and what nosotros desire to our partner, which will promote greater agreement and satisfaction. As well, perhaps when we feel clearer about who we are, then nosotros feel less of a threat to our self-concept and autonomy when we find ourselves having to make compromises in our shut relationships.

Thinking back to the cultural differences we discussed earlier in this section in the context of people's self-concepts, it could be that cocky-concept clarity is more often than not college in individuals from individualistic cultures, as their self-concept is based more on internal characteristics that are held to exist stable across situations, than on external social facets of the self that may be more than changeable. This is indeed what the enquiry suggests. Not simply do members of more than collectivistic cultures tend to take lower self-concept clarity, that clarity is too less strongly related to their cocky-esteem compared with those from more individualistic cultures (Campbell et al., 1996). As nosotros shall see when our attending turns to perceiving others in Chapter five, our cultural background not only affects the clarity and consistency of how we see ourselves, but also how consistently we view other people and their behavior.

Self-Awareness

Like any other schema, the cocky-concept tin can vary in its electric current cognitive accessibility. Self-awareness refers to the extent to which we are currently fixing our attention on our ain self-concept. When our self-concept becomes highly attainable because of our concerns virtually being observed and potentially judged past others, we experience the publicly induced self-awareness known every bit cocky-consciousness (Duval & Wicklund, 1972; Rochat, 2009).

Perhaps yous tin think times when your self-awareness was increased and you became cocky-conscious—for instance, when you were giving a presentation and y'all were peradventure painfully aware that everyone was looking at you, or when you did something in public that embarrassed yous. Emotions such as anxiety and embarrassment occur in large office because the self-concept becomes highly accessible, and they serve as a signal to monitor and mayhap change our behavior.

Non all aspects of our self-concept are as accessible at all times, and these long-term differences in the accessibility of the different self-schemas assist create individual differences in terms of, for example, our current concerns and interests. You may know some people for whom the physical advent component of the self-concept is highly attainable. They check their pilus every fourth dimension they come across a mirror, worry whether their clothes are making them wait good, and do a lot of shopping—for themselves, of course. Other people are more focused on their social group memberships—they tend to remember about things in terms of their role as Muslims or Christians, for example, or as members of the local tennis or soccer squad.

In improver to variation in long-term accessibility, the self and its various components may also be made temporarily more attainable through priming. We get more self-aware when we are in front of a mirror, when a Idiot box camera is focused on usa, when we are speaking in front of an audience, or when we are listening to our own record-recorded vocalism (Kernis & Grannemann, 1988). When the knowledge contained in the self-schema becomes more accessible, it also becomes more than likely to be used in information processing and to influence our behavior.

Beaman, Klentz, Diener, and Svanum (1979) conducted a field experiment to see if self-awareness would influence children'south honesty. The researchers expected that most children viewed stealing as wrong simply that they would be more likely to act on this belief when they were more self-aware. They conducted this experiment on Halloween in homes inside the metropolis of Seattle, Washington. At detail houses, children who were trick-or-treating were greeted by one of the experimenters, shown a large bowl of candy, and were told to take only one slice each. The researchers unobtrusively watched each child to come across how many pieces he or she actually took. In some of the houses there was a large mirror behind the candy bowl; in other houses, in that location was no mirror. Out of the 363 children who were observed in the study, nineteen% disobeyed instructions and took more than one piece of candy. Yet, the children who were in front of a mirror were significantly less likely to steal (14.iv%) than were those who did not see a mirror (28.5%).

These results suggest that the mirror activated the children's cocky-awareness, which reminded them of their belief near the importance of being honest. Other research has shown that existence self-aware has a powerful influence on other behaviors likewise. For instance, people are more than probable to stay on a nutrition, eat improve food, and act more morally overall when they are self-aware (Baumeister, Zell, & Tice, 2007; Heatherton, Polivy, Herman, & Baumeister, 1993). What this means is that when yous are trying to stick to a diet, study harder, or engage in other difficult behaviors, you should endeavor to focus on yourself and the importance of the goals you have set up.

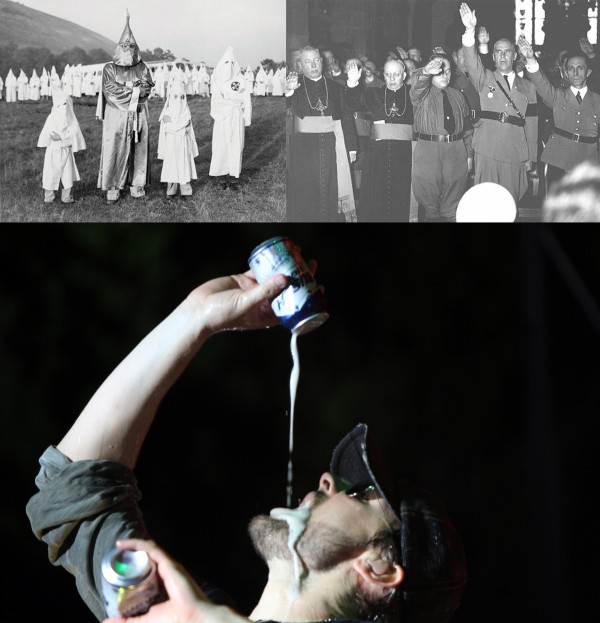

Social psychologists are interested in studying self-sensation because it has such an important influence on beliefs. People become more likely to violate acceptable, mainstream social norms when, for example, they put on a Halloween mask or engage in other behaviors that hide their identities. For case, the members of the militant White supremacist organisation the Ku Klux Klan wear white robes and hats when they run across and when they engage in their racist behavior. And when people are in large crowds, such as in a mass demonstration or a riot, they may get so much a part of the grouping that they feel deindividuation—the loss of individual cocky-awareness and individual accountability in groups (Festinger, Pepitone, & Newcomb, 1952; Zimbardo, 1969) and become more attuned to themselves as group members and to the specific social norms of the particular situation (Reicher & Stott, 2011).

08KKKfamilyPortrait past Image Editor (http://www.flickr.com/photos/11304375@N07/2534972038) used under CC BY ii.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/2.0/). Catholic clergy and Nazi official (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CatholicClergyAndNaziOfficials.jpg) is in the public domain. Eric Church by Larry Darling (https://www.flickr.com/photos/tncountryfan/6171754005/) used under CC BY-NC 2.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/ii.0/)

Social Psychology in the Public Interest

Deindividuation and Rioting

Rioting occurs when civilians engage in fierce public disturbances. The targets of these disturbances tin exist people in say-so, other civilians, or property. The triggers for riots are varied, including everything from the aftermath of sporting events, to the killing of a civilian by law enforcement officers, to commodity shortages, to political oppression. Both civilians and law enforcement personnel are often seriously injured or killed during riots, and the harm to public property tin can exist considerable.

Social psychologists, like many other academics, have long been interested in the forces that shape rioting behavior. One of the earliest and most influential perspectives on rioting was offered by French sociologist, Gustav Le Bon (1841–1931). In his book The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Heed, Le Bon (1895) described the transformation of the individual in the crowd. Co-ordinate to Le Bon, the forces of anonymity, suggestibility, and contamination combine to change a collection of individuals into a "psychological crowd." Under this view, the individuals and so become submerged in the crowd, lose self-control, and engage in antisocial behaviors.

Some of the early social psychological accounts of rioting focused in particular on the concept of deindividuation as a mode of trying to business relationship for the forces that Le Bon described. Festinger et al. (1952), for instance, argued that members of big groups exercise not pay attention to other people as individuals and practise not feel that their ain behavior is being scrutinized. Nether this view, being unidentified and thereby unaccountable has the psychological consequence of reducing inner restraints and increasing behavior that is usually repressed, such as that often seen in riots.

Extending these ideas, Zimbardo (1969) argued that deindividuation involved feelings of reduced cocky-ascertainment, which then bring about antinormative and disinhibited behavior. In support of this position, he plant that participants engaged in more antisocial behavior when their identity was made anonymous by wearing Ku Klux Klan uniforms. Still, in the context of rioting, these perspectives, which focus on behaviors that are antinormative (east.g., aggressive behavior is typically antinormative), neglect the possibility that they might actually be normative in the particular situation. For instance, during some riots, antisocial beliefs can be viewed every bit a normative response to injustice or oppression. Consistent with this assertion, Johnson and Downing (1979) found that when participants were able to mask their identities by wearing nurses uniforms, their deindividuated state actually led them to show more than prosocial behavior than when their identities were visible to others. In other words, if the grouping state of affairs is associated with more prosocial norms, deindividuation can actually increase these behaviors, and therefore does non inevitably lead to antisocial carry.

Building on these findings, researchers have developed more contemporary accounts of deindividuation and rioting. One specially of import arroyo has been the social identity model of deindividuation effects (or SIDE model), developed by Reicher, Spears, and Postmes (1995). This perspective argues that existence in a deindividuated state tin actually reinforce group salience and conformity to specific grouping norms in the current state of affairs. According to this model, deindividuation does not, then, atomic number 82 to a loss of identity per se. Instead, people take on a more collective identity. Seen in this mode, rioting behavior is more nearly the conscious adoption of behaviors reflecting collective identity than the abdication of personal identity and responsibility outlined in the earlier perspectives on deindividuation.

In support of the SIDE model, although crowd behavior during riots might seem mindless, antinormative, and disinhibited to the outside observer, to those taking role it is often perceived as rational, normative, and bailiwick to well-divers limits (Reicher, 1987). For case, when law enforcement officers are the target of rioters, then any targeting of other civilians by rioters is often condemned and policed by the grouping members themselves (Reicher & Stott, 2011). Indeed, as Fogelson (1971) concluded in his analysis of rioting in the United states of america in the 1960s, restraint and selectivity, as opposed to mindless and indiscriminate violence, were among the most crucial features of the riots.

Seeing rioting in this way, as a rational, normative response, Reicher and Stott (2011) draw it every bit existence acquired by a number of interlocking factors, including a sense of illegitimacy or grievance, a lack of alternatives to confrontation, the formation of a shared identity, and a sense of confidence in collective power. Viewing deindividuation every bit a force that causes people to increase their sense of collective identity and then to express that identity in meaningful ways leads to some important recommendations for decision-making rioting more effectively, including that:

- Labeling rioters equally "mindless," "thugs," and and so on will not address the underlying causes of riots.

- Indiscriminate or disproportionate employ of forcefulness by police will oft atomic number 82 to an escalation of rioting behavior.

- Law enforcement personnel should permit legitimate and legal protestation behaviors to occur during riots, and simply illegal and inappropriate behaviors should be targeted.

- Constabulary officers should communicate their intentions to crowds before using force.

Tellingly, in analyses of the policing of high-risk rioting situations, when police follow these guidelines, riots are often prevented altogether, or at least de-escalated relatively speedily (Reicher & Stott, 2011). Thus, the social psychological research on deindividuation has not only helped the states to refine our understanding of this concept, but has too led us to better sympathize the social dynamics of rioting behavior. Ultimately, this increased understanding has helped to put more effective strategies in place for reducing the risks to people and property that riots bring.

2 aspects of individual differences in self-sensation have been constitute to be important, and they relate to self-business and other-concern, respectively (Fenigstein, Scheier, & Kiss, 1975; Lalwani, Shrum, & Chiu, 2009).Individual self-consciousness refers to the tendency to introspect about our inner thoughts and feelings. People who are high in private self-consciousness tend to call back about themselves a lot and hold with statements such as "I'm always trying to effigy myself out" and "I am generally attentive to my inner feelings." People who are high on private self-consciousness are probable to base their behavior on their own inner beliefs and values—they allow their inner thoughts and feelings guide their deportment—and they may exist peculiarly probable to strive to succeed on dimensions that allow them to demonstrate their ain personal accomplishments (Lalwani et al., 2009).

Public self-consciousness, in contrast, refers to the tendency to focus on our outer public prototype and to be particularly aware of the extent to which we are meeting the standards set up past others. Those loftier in public self-consciousness agree with statements such as "I'k concerned about what other people recollect of me," "Before I leave my house, I cheque how I look," and "I care a lot about how I present myself to others." These are the people who check their hair in a mirror they pass and spend a lot of time getting ready in the morning; they are more likely to let the opinions of others (rather than their own opinions) guide their behaviors and are peculiarly concerned with making practiced impressions on others.

Research has found cultural differences in public self-consciousness, with people from Due east Asian, collectivistic cultures having higher public cocky-consciousness than people from Western, individualistic cultures. Steve Heine and colleagues (2008) found that when college students from Canada (a Western culture) completed questionnaires in front end of a large mirror, they subsequently became more than self-critical and were less probable to cheat (much like the trick-or-treaters discussed earlier) than were Canadian students who were not in front end of a mirror. Notwithstanding, the presence of the mirror had no consequence on college students from Nippon. This person-situation interaction is consistent with the thought that people from East Asian cultures are normally already loftier in public cocky-consciousness compared with people from Western cultures, and thus manipulations designed to increment public self-consciousness influence them less.

Then we run into that in that location are conspicuously individual and cultural differences in the degree to and fashion in which we tend to exist enlightened of ourselves. In general, though, we all experience heightened moments of cocky-awareness from time to fourth dimension. Co-ordinate to self-awareness theory(Duval & Wicklund, 1972), when nosotros focus our attention on ourselves, nosotros tend to compare our electric current behavior confronting our internal standards. Sometimes when we make these comparisons, we realize that we are non currently measuring upwards. In these cases,self-discrepancy theory states that when nosotrosperceive a discrepancy between our actual and ideal selves, this is distressing to the states(Higgins, Klein, & Strauman, 1987). In dissimilarity, on the occasions when self-awareness leads united states of america to comparisons where nosotros experience that weare being congruent with our standards, so self-awareness tin produce positive affect (Greenberg & Musham, 1981). Tying these ideas from the two theories together, Philips and Silvia (2005) institute that people felt significantly more distressed when exposed to self-discrepancies while sitting in front of a mirror. In contrast, those not sitting in forepart of a mirror, and presumably experiencing lower cocky-sensation, were non significantly emotionally affected by perceived self-discrepancies. Merely put, the more than self-aware we are in a given situation, the more pain nosotros feel when nosotros are non living up to our ideals.

In part, the stress arising from perceived self-discrepancy relates to a sense ofcerebral noise, which is the discomfort that occurs when nosotros respond in ways that we see every bit inconsistent. In these cases, nosotros may realign our current state to be closer to our ideals, or shift our ideals to exist closer to our current state, both of which will help reduce our sense of dissonance. Another potential response to feelings of self-discrepancy is to try to reduce the state of self-awareness that gave rise to these feelings by focusing on other things. For example, Moskalenko and Heine (2002) found that people who are given fake negative feedback about their performance on an intelligence test, which presumably atomic number 82 them to feel discrepant from their internal performance standards nearly such tasks, subsequently focused significantly more on a video playing in a room than those given positive feedback.

There are certain situations, however, where these common noise-reduction strategies may not exist realistic options to pursue. For instance, if someone who has generally negative attitudes toward drug utilise nonetheless becomes addicted to a particular substance, it volition often not be easy to quit the habit, to reframe the evidence regarding the drug'southward negative furnishings, or to reduce self-awareness. In such cases,self-affidavit theorysuggests that people will try to reduce the threat to their self-concept posed past feelings of self-discrepancy by focusing on and affirming their worth in another domain, unrelated to the outcome at hand. For instance, the person who has get addicted to an illegal substance may choose to focus on good for you eating and exercise regimes instead as a way of reducing the noise created by the drug use.

Although cocky-affidavit can oftentimes help people feel more than comfy by reducing their sense of noise, information technology can also have have some negative effects. For example, Munro and Stansbury (2009) tested people's social cognitive responses to hypotheses that were either threatening or not-threatening to their self-concepts, following exposure to either a cocky-affirming or non-affirming activeness. The key findings were that those who had engaged in the self-affirmation condition and were then exposed to a threatening hypothesis showed greater tendencies than those in the non-affirming group to seek out testify confirming their own views, and to find illusory correlations in support of these positions. One possible interpretation of these results is that self-affidavit elevates people's mood and they then become more likely to appoint in heuristic processing, equally discussed in Affiliate 2.

Still another option to pursue when nosotros feel that our electric current cocky is not matching upwards to our ideal self is to seek out opportunities to become closer to our ideal selves. Ane method of doing this can be in online environments. Massively multiplayer online (MMO) gaming, for instance, offers people the chance to collaborate with others in a virtual globe, using graphical alter egos, or avatars, to stand for themselves. The function of the self-concept in influencing people'due south choice of avatars is only merely beginning to be researched, simply some show suggests that gamers blueprint avatars that are closer to their ideal than their actual selves. For instance, a written report of avatars used in ane popular MMO function-play game indicated that players rated their avatars every bit having more than favorable attributes than their ain cocky-ratings, particularly if they had lower self-esteem (Bessiere, Seay, & Keisler, 2007). They also rated their avatars as more similar to their ideal selves than they themselves were. The authors of this study ended that these online environments let players to explore their ideal selves, freed from the constraints of the physical globe.

There are also emerging findings exploring the role of cocky-awareness and self-affirmation in relation to behaviors on social networking sites. Gonzales and Hancock (2011) conducted an experiment showing that individuals became more cocky-enlightened after viewing and updating their Facebook profiles, and in turn reported higher self-esteem than participants assigned to an offline, command condition. The increased self-awareness that can come from Facebook activity may not always have beneficial effects, notwithstanding. Chiou and Lee (2013) conducted two experiments indicating that when individuals put personal photos and wall postings onto their Facebook accounts, they show increased self-awareness, merely subsequently decreased power to take other people's perspectives. Maybe sometimes we tin have besides much cocky-sensation and focus to the detriment of our abilities to sympathise others. Toma and Hancock (2013) investigated the role of self-affirmation in Facebook usage and found that users viewed their profiles in self-affirming ways, which enhanced their self-worth. They were besides more likely to look at their Facebook profiles subsequently receiving threats to their cocky-concept, doing so in an attempt to use self-affirmation to restore their self-esteem. It seems, then, that the dynamics of self-awareness and affidavit are quite similar in our online and offline behaviors.

Having reviewed some of import theories and findings in relation to self-discrepancy and affirmation, nosotros should now turn our attention to diversity. Over again, as with many other aspects of the self-concept, we find that there are of import cultural differences. For case, Heine and Lehman (1997) tested participants from a more than individualistic nation (Canada) and a more collectivistic one (Japan) in a situation where they took a personality test and then received bogus positive or negative feedback. They were and so asked to rate the desirability of 10 music CDs. Afterwards, they were offered the choice of taking dwelling either their fifth- or sixth-ranked CD, and and then required to re-rate the 10 CDs. The critical finding was that the Canadians overall rated their chosen CD higher and their unchosen 1 lower the 2nd fourth dimension effectually, mirroring classic findings on dissonance reduction, whereas the Japanese participants did non. Crucially, though, the Canadian participants who had been given positive feedback about their personalities (in other words, had been given self-affirming prove in an unrelated domain) did not feel the need to pursue this dissonance reduction strategy. In contrast, the Japanese did not significantly conform their ratings in response to either positive or negative feedback from the personality test.

Once again, these findings brand sense if we consider that the pressure level to avoid self-discrepant feelings will tend to be higher in individualistic cultures, where people are expected to be more cantankerous-situationally consistent in their behaviors. Those from collectivistic cultures, however, are more accepted to shifting their behaviors to fit the needs of the ingroup and the situation, and so are less troubled by such seeming inconsistencies.

Overestimating How Closely and Accurately Others View U.s.

Although the cocky-concept is the virtually important of all our schemas, and although people (especially those loftier in self-consciousness) are aware of their cocky and how they are seen by others, this does not mean that people are e'er thinking about themselves. In fact, people do not generally focus on their self-concept whatever more than they focus on the other things and other people in their environments (Csikszentmihalyi & Figurski, 1982).

On the other manus, self-awareness is more powerful for the person experiencing it than it is for others who are looking on, and the fact that cocky-concept is and then highly accessible often leads people to overestimate the extent to which other people are focusing on them (Gilovich & Savitsky, 1999). Although you may be highly cocky-conscious about something you've done in a particular state of affairs, that does not mean that others are necessarily paying all that much attention to you. Inquiry by Thomas Gilovich and colleagues (Gilovich, Medvec, & Savitsky, 2000) found that people who were interacting with others thought that other people were paying much more attention to them than those other people reported really doing. This may be welcome news, for example, when we discover ourselves wincing over an embarrassing comment nosotros made during a grouping chat. It may well exist that no one else paid nearly as much attention to information technology as we did!

There is also some diversity in relation to age. Teenagers are particularly likely to be highly self-conscious, often believing that others are watching them (Goossens, Beyers, Emmen, & van Aken, 2002). Because teens retrieve then much about themselves, they are specially likely to believe that others must be thinking about them, too (Rycek, Stuhr, McDermott, Benker, & Swartz, 1998). Viewed in this light, it is perhaps not surprising that teens can become embarrassed so easily by their parents' behaviour in public, or by their own physical advent, for example.

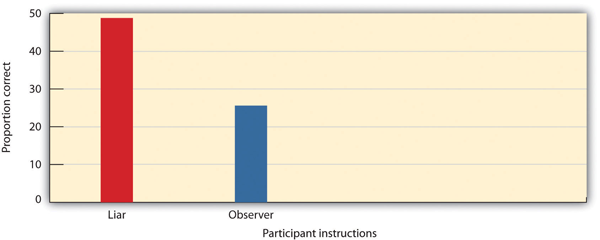

People besides often mistakenly believe that their internal states show to others more than than they really do. Gilovich, Savitsky, and Medvec (1998) asked groups of five students to work together on a "lie detection" task. I at a fourth dimension, each pupil stood upwards in front of the others and answered a question that the researcher had written on a menu (due east.g., "I have met David Letterman"). On each circular, one person's card indicated that they were to give a false answer, whereas the other four were told to tell the truth.

After each circular, the students who had non been asked to prevarication indicated which of the students they thought had actually lied in that round, and the liar was asked to estimate the number of other students who would correctly guess who had been the liar. As you lot can come across in Figure 3.vii, "The Illusion of Transparency," the liars overestimated the detectability of their lies: on average, they predicted that over 44% of their boyfriend players had known that they were the liar, but in fact only about 25% were able to accurately identify them. Gilovich and colleagues called this effect the "illusion of transparency." This illusion brings habitation an important last learning signal nigh our cocky-concepts: although we may experience that our view of ourselves is obvious to others, information technology may not e'er be!

- The self-concept is a schema that contains knowledge about us. Information technology is primarily made up of physical characteristics, group memberships, and traits.

- Considering the self-concept is so complex, it has extraordinary influence on our thoughts, feelings, and beliefs, and we tin remember information that is related to information technology well.

- Self-complexity, the extent to which individuals have many different and relatively independent ways of thinking about themselves, helps people answer more positively to events that they feel.

- Self-concept clarity, the extent to which individuals have cocky-concepts that are conspicuously defined and stable over time, can also assistance people to respond more positively to challenging situations.

- Self-sensation refers to the extent to which nosotros are currently fixing our attention on our ain self-concept. Differences in the accessibility of unlike cocky-schemas help create individual differences: for instance, in terms of our electric current concerns and interests.

- People who are experiencing loftier self-awareness may find cocky-discrepancies between their actual and ideal selves. This tin can, in turn, pb them to engage in self-affidavit as a way of resolving these discrepancies.

- When people lose their cocky-sensation, they experience deindividuation.

- Individual self-consciousness refers to the trend to introspect nigh our inner thoughts and feelings; public self-consciousness refers to the trend to focus on our outer public prototype and the standards set up past others.

- At that place are cultural differences in cocky-consciousness: public self-consciousness may exist higher in Eastern than in Western cultures.

- People frequently overestimate the extent to which others are paying attention to them and accurately understand their true intentions in public situations.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- What are the about important aspects of your self-concept, and how do they influence your self-esteem and social behavior?

- Consider people you know who vary in terms of their self-complexity and self-concept clarity. What furnishings do these differences seem to take on their self-esteem and behavior?

- Draw a situation where you experienced a feeling of self-discrepancy between your bodily and ideal selves. How well does self-affidavit theory assist to explicate how y'all responded to these feelings of discrepancy?

- Attempt to identify some situations where you have been influenced by your private and public self-consciousness. What did this lead y'all to practise? What have you learned about yourself from these experiences?

- Describe some situations where you overestimated the extent to which people were paying attention to y'all in public. Why do you lot remember that you did this and what were the consequences?

References

Asendorpf, J. B., Warkentin, V., & Baudonnière, P-M. (1996). Self-awareness and other-sensation. Two: Mirror self-recognition, social contingency awareness, and synchronic false.Developmental Psychology, 32(ii), 313–321.

Barrios, V., Kwan, 5. S. Y., Ganis, 1000., Gorman, J., Romanowski, J., & Keenan, J. P. (2008). Elucidating the neural correlates of egoistic and moralistic self-enhancement.Consciousness and Cognition: An International Journal, 17(2), 451–456.

Baumeister, R. F., Zell, A. L., & Tice, D. M. (2007). How emotions facilitate and impair self-regulation. In J. J. Gross & J. J. E. Gross (Eds.),Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 408–426). New York, NY: Guilford Printing.

Beaman, A. L., Klentz, B., Diener, E., & Svanum, South. (1979). Self-awareness and transgression in children: Two field studies.Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(x), 1835–1846.

Bessiere, K., Seay, A. F., & Kiesler, S. (2007). The ideal elf: Identity exploration in Earth of Warcraft.Cyberpsychology and Behavior: The Bear upon of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 10(4),530-535.

Boysen, S. T., & Himes, G. T. (1999). Electric current issues and emerging theories in animal knowledge.Almanac Review of Psychology, fifty, 683–705.

Campbell, J. D. (1990). Self-esteem and clarity of the self-concept.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59,538-549.

Campbell, J. D., Trapnell, P. D., Heine, S. J., Katz, I. One thousand., Lavalle, 50. F., & Lehman, D. R. (1996). Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries.Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology, 70,141-156.

Chiou, W., & Lee, C. (2013). Enactment of one-to-many communication may induce self-focused attention that leads to diminished perspective taking: The case of Facebook.Judgment And Determination Making,viii(3), 372-380.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Figurski, T. J. (1982). Self-awareness and aversive experience in everyday life.Journal of Personality, 50(one), fifteen–28.

DeAndrea, D. C., Shaw, A. S., & Levine, T. R. (2010). Online linguistic communication: The role of culture in self-expression and self-construal on Facebook.Journal Of Language And Social Psychology,29(iv), 425-442. doi:10.1177/0261927X10377989

Doherty, M. J. (2009).Theory of mind: How children understand others' thoughts and feelings. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Duval, S., & Wicklund, R. A. (1972).A theory of objective self-awareness. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Fenigstein, A., Scheier, M. F., & Buss, A. H. (1975). Public and private cocky-consciousness: Assessment and theory.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43, 522–527.

Festinger, L., Pepitone, A., & Newcomb, B. (1952). Some consequences of deindividuation in a group.Journal of Aberrant and Social Psychology, 47, 382–389.

Fogelson, R. M. (1971). Violence as protest: A written report of riots and ghettos. New York: Anchor.

Gallup, G. G., Jr. (1970). Chimpanzees: self-recognition.Science, 167, 86–87.

Gilovich, T., & Savitsky, Grand. (1999). The spotlight effect and the illusion of transparency: Egocentric assessments of how nosotros are seen by others.Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8(6), 165–168.

Gilovich, T., Medvec, V. H., & Savitsky, K. (2000). The spotlight effect in social judgment: An egocentric bias in estimates of the salience of one'due south own deportment and appearance.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 211–222.

Gilovich, T., Savitsky, K., & Medvec, V. H. (1998). The illusion of transparency: Biased assessments of others' ability to read i's emotional states.Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(ii), 332–346.

Gonzales, A. L., & Hancock, J. T. (2011). Mirror, mirror on my Facebook wall: Furnishings of exposure to Facebook on self-esteem.Cyberpsychology, Behavior, And Social Networking,14(1-2), 79-83. doi:x.1089/cyber.2009.0411

Goossens, L., Beyers, W., Emmen, One thousand., & van Aken, M. (2002). The imaginary audience and personal fable: Factor analyses and concurrent validity of the "new wait" measures.Journal of Research on Boyhood, 12(2), 193–215.

Gramzow, R. H., Sedikides, C., Panter, A. T., & Insko, C. A. (2000). Aspects of self-regulation and self-structure as predictors of perceived emotional distress.Personality and Social Psychology Message, 26, 188–205.

Greenberg, J., & Musham, C. (1981). Avoiding and seeking self-focused attending.Periodical of Research in Personality, 15,191-200.

Harter, S. (1998). The evolution of self-representations. In W. Damon & N. Eisenberg (Eds.),Handbook of kid psychology: Social, emotional, & personality development (5th ed., Vol. iii, pp. 553–618). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Harter, S. (1999).The construction of the self: A developmental perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Printing.

Heatherton, T. F., Polivy, J., Herman, C. P., & Baumeister, R. F. (1993). Cocky-awareness, chore failure, and disinhibition: How attentional focus affects eating.Journal of Personality, 61, 138–143.

Heine, S. J., and Lehman, D. R. (1997). Culture, racket, and self-affirmation.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23,389-400.

Heine, South. J., Takemoto, T., Moskalenko, Southward., Lasaleta, J., & Henrich, J. (2008). Mirrors in the head: Cultural variation in objective cocky-awareness.Personality and Social Psychology Message, 34(7), 879–887.

Higgins, E. T., Klein, R., & Strauman, T. (1987). Self-discrepancies: Distinguishing among self-states, self-land conflicts, and emotional vulnerabilities. In K. G. Yardley & T. Thou. Honess (Eds.),Self and identity: Psychosocial perspectives.(pp. 173-186). New York: Wiley.

Ip, G. Westward. M., & Bond, 1000. H. (1995). Culture, values, and the spontaneous self-concept.Asian Journal of Psychology,1, 29-35.

Johnson, R. D. & Downing, L. Fifty. (1979). Deindividuation and valence of cues: Furnishings of prosocial and antisocial behavior. Periodical of Personality & Social Psychology, 37, 1532-1538 x.1037//0022-3514 .37.9.1532.

Kalthoff, R. A., & Neimeyer, R. A. (1993). Self-complexity and psychological distress: A test of the buffering model.International Periodical of Personal Construct Psychology, six(4), 327–349.

Kashima, Y., Yamaguchi, S., Kim, U., Choi, S., Gelfank, M., & Yuki, M. (1995). Civilisation, gender, and cocky: A perspective from individualism-collectivism inquiry.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69,925-937.

Kernis, M. H., & Grannemann, B. D. (1988). Private self-consciousness and perceptions of self-consistency.Personality and Individual Differences, nine(5), 897–902.

Kim, H., & Markus, H. (1999). Deviance or uniqueness, harmony or conformity? A cultural analysis.Periodical Of Personality And Social Psychology,77(4), 785-800. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.iv.785

Koch, E. J., & Shepperd, J. A. (2004). Is self-complication linked to meliorate coping? A review of the literature.Journal of Personality, 72(4), 727–760.

Lalwani, A. K., Shrum, L. J., & Chiu, C-Y. (2009). Motivated response styles: The office of cultural values, regulatory focus, and self-consciousness in socially desirable responding.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 870–882.

Le Bon, 1000. (1895). The oversupply: A study of the popular mind.Project Gutenberg.

Lewandowski, G. R., Nardon, Northward., Raines, A. J. (2010). The office of self-concept clarity in relationship quality.Self and Identity, 9(4),416-433.

Lieberman, Thou. D. (2010). Social cerebral neuroscience. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.),Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. one, pp. 143–193). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Lieberman, Thousand. D., Jarcho, J. Thou., & Satpute, A. B. (2004). Evidence-based and intuition-based self-knowledge: An fMRI study.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(iv), 421–435.

Linville, P. W. (1987). Self-complexity as a cognitive buffer confronting stress-related affliction and low.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(four), 663–676.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the cocky: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation.Psychological Review,98(2), 224-253. doi:x.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

McConnell, A. R., Renaud, J. G., Dean, One thousand. K., Green, South. P., Lamoreaux, One thousand. J., Hall, C. Due east.,…Rydel, R. J. (2005). Whose self is it anyway? Cocky-attribute control moderates the relation between self-complexity and well-being.Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(ane), i–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2004.02.004

McGuire, W. J., McGuire, C. V., Child, P., & Fujioka, T. (1978). Salience of ethnicity in the spontaneous self-concept equally a function of 1's ethnic distinctiveness in the social enviornment.Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology, 36, 511–520.

Moskalenko, Southward., & Heine, Southward. J. (2002). Watching your troubles away: Television set viewing as a stimulus for subjective self-awareness.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29,76-85.

Munro, G. D., & Stansbury, J. A. (2009). The nighttime side of self-affidavit: Confirmation bias and illusory correlation in response to threatening information.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(9),1143-1153.

Nisbett, R. E. (2003).The geography of thought.New York, NY: Costless Press.

Oyserman, D., Bybee, D., Terry, 1000., & Hart-Johnson, T. (2004). Possible selves equally roadmaps.Journal of Research in Personality, 38(2), 130–149.

Phillips, A. M., & Silvia, P. J. (2005). Self-Awareness and the Emotional Consequences of Self-Discrepancies.Personality And Social Psychology Message,31(v), 703-713. doi:10.1177/0146167204271559

Povinelli, D. J., Landau, K. R., & Perilloux, H. One thousand. (1996). Self-recognition in young children using delayed versus live feedback: Testify of a developmental asynchrony.Child Development, 67(four), 1540–1554.

Rafaeli-Mor, E., & Steinberg, J. (2002). Self-complexity and well-beingness: A review and research synthesis.Personality and Social Psychology Review, vi, 31–58.

Reicher, Due south. D. (1987). Crowd behaviour equally social activity. In J. C. Turner, 1000. A. Hogg, P. J. Oakes, Southward. D. Reicher, & G. S. Wetherell (Eds.), Rediscovering the social grouping: A self-categorization theory (pp. 171–202). Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell

Reicher, Southward. D., Spears, R., & Postmes, T. (1995). A social identity model of deindividuation phenomena. In Due west. Strobe & M. Hewstone

(Eds.), European review of social psychology (pp.161-198). Chichester, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Wiley.

Reicher, S., & Stott, C. (2011).Mad mobs and Englishmen? Myths and realities of the 2011 riots.London: Constable and Robinson.

Rees, A., & Nicholson, Northward. (1994). The Twenty Statements Test. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.),Qualitative methods in organizational research: A applied guide (pp. 37–54).

Ritchie, T. D., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Arndt, J., & Gidron, Y. (2011). Self-concept clarity mediates the relation betwixt stress and subjective well-being.Cocky and Identity, 10(4),493-508.

Roccas, S., & Brewer, Yard. (2002). Social identity complexity.Personality and Social Psychology Review, half-dozen(ii), 88–106.

Rochat, P. (2009).Others in heed: Social origins of self-consciousness. New York, NY: Cambridge University Printing.

Rogers, T. B., Kuiper, North. A., & Kirker, Westward. S. (1977). Self-reference and the encoding of personal data.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(nine), 677–688.

Ross, M., Xun, W. Q., & Wilson, A. East. (2002). Language and the bicultural self.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28,1040-1050.

Rycek, R. F., Stuhr, S. L., McDermott, J., Benker, J., & Swartz, K. D. (1998). Adolescent egocentrism and cognitive performance during late boyhood.Adolescence, 33, 746–750.

Toma, C. L., & Hancock, J. T. (2013). Self-affidavit underlies Facebook use.Personality And Social Psychology Bulletin,39(iii), 321-331. doi:ten.1177/0146167212474694

Watkins, D., Akande, A. , Fleming, J., Ismail, K., Lefner, Chiliad., Regmi, Thousand., Watson, S., Yu, J., Adair, J., Cheng, C., Gerong, A., McInerney, D., Mpofu, E., Sinch-Sengupta, Southward., & Wondimu, H. (1998). Cultural dimensions, gender, and the nature of self-concept: A fourteen-country study.International Periodical of Psychology, 33,17-31.

Zimbardo, P. (1969). The human being choice: Individuation, reason and society versus deindividuation impulse and anarchy. In W. J. Arnold & D. Levine (Eds.),Nebraska Symposium of Motivation (Vol. 17). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Source: https://opentextbc.ca/socialpsychology/chapter/the-cognitive-self-the-self-concept/

Posted by: wardhoulds.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Is An Entity More Likely To Attach Itself To A Person An Animal Or An Object"

Post a Comment